Faith still a potent presence in UK politics, says author

Faith still a potent presence in UK politics, says author

idea that secularisation would purge politics of religious commitment appears misguided, Nick Spencer’s book argues

Confidence remains an intense nearness at the largest amount of UK legislative issues in spite of a developing extent of the nation's populace characterizing themselves as non-religious, as indicated by the writer of another book inspecting the confidence of noticeable government officials.

Scratch Spencer, look into chief of the Theos research organization and the lead creator of The Mighty and the Almighty: How Political Leaders Do God, utilizes the case that everything except one of Britain's six PMs in the previous four decades have been rehearsing Christians to make his point.

The book looks at the confidence of 24 noticeable government officials, generally in Europe, the US and Australia, since 1979. "The nearness and commonness of Christian pioneers, not minimum in a portion of the world's most mainstream, plural and "present day" nations, stays vital. The possibility that "secularization" would cleanse legislative issues of religious responsibility is without a doubt confused," it finishes up.

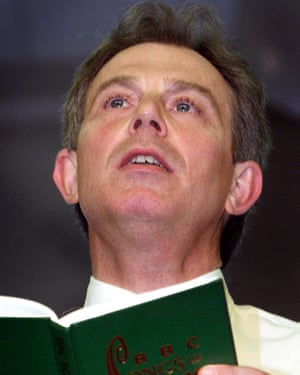

It incorporates "theo-political histories" of Theresa May, an Anglican vicar's little girl who has talked openly about her Christianity since taking office last July, and her ancestors David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair and Margaret Thatcher. Just John Major is truant from the post-1979 lineup.

Spencer composes that May is a "lawmaker with solid perspectives as opposed to a solid belief system, and those perspectives were apparently molded by her Christian childhood and confidence. That Christianity gives her, in her own words, 'an ethical support to what I do, and I would trust that the choices I take are gone up against the premise of my confidence'."

May disclosed to Desert Island Disks in 2014 that Christianity had surrounded her reasoning however it was "correct that we don't parade these things here in British governmental issues". As indicated by Spencer, "in such manner in any event, May tries doing she proposes for others to do".

In any case, the PM's clear hesitance did not stop her assailing Cadbury's and the National Trust this month over their gathered downsizing of the word Easter in limited time

Somewhere else, the book takes a gander at five US presidents – Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W Bush, Barack Obama and Donald Trump – five European pioneers, three Australian PMs and Vladimir Putin of Russia. Five pioneers from different nations – including Nelson Mandela – finish the rundown.

The "colossal mainstream expectation" was that religion would grow dim of the political scene, Spencer composes. In any case, "the most recent 40 years have turned out to some degree distinctive", with the rise of political Islam, the quality of Catholicism in focal and south America and the blast of Pentecostalism in the worldwide south.

Indeed, even in the west, "Christian political pioneers have barely turned out to be less noticeable over late decades, and may, truth be told, have turned out to be all the more so," he says.

Be that as it may, Spencer told the Guardian: "There is nobody measure fits all, politically. You don't discover them bunching on the political range."

At the conservative end were Thatcher and Reagan. At the other was Fernando Lugo, the leader of Paraguay in the vicinity of 2008 and 2012, an unmistakable Catholic "minister of poor people", freedom theologist and some portion of an influx of leftwing pioneers in Latin America.

There were likewise critical contrasts in the political settings in which Christian lawmakers were working, Spencer said. "There are spots where you remain to make a ton of political capital by discussing your confidence –, for example, the US or Russia.

"Be that as it may, in nations like the UK, Australia, Germany, France, where electorates are hyper-distrustful, lawmakers remain to lose political capital. No lawmaker in the UK or France discusses their confidence with a specific end goal to charm the electorate."

Blair’s communications chief Alastair Campbell famously warned a television interviewer against asking the then prime minister about his faith, saying: “We don’t do God.” He believed the British public was instinctively distrustful of religiously-minded politicians.

Comments

Post a Comment